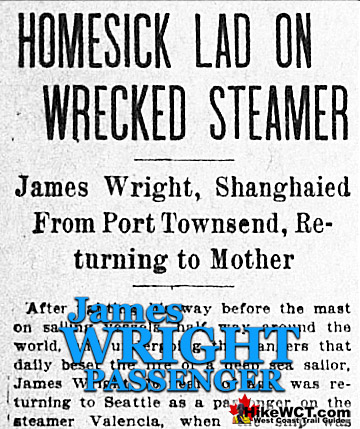

James Wright - Second-Class Passenger

James Floyd Wright was a sixteen-year-old second-class passenger on the Valencia. On the night of 22 January 1906, the Pacific Coast Steamship Company’s steamer SS Valencia struck a reef off Vancouver Island and broke apart in heavy seas. Of the roughly 110 passengers and 65 crew aboard, only 38 would survive. Among the estimated 137 souls lost was a slight, homesick sixteen-year-old boy from Seattle named James Floyd Wright, whose body, like so many others, was never recovered. James’s story is not one of heroic sacrifice or high adventure, but of a child caught up in the brutal realities of the maritime world at the turn of the century, and of a mother’s desperate hope that ended in heartbreak just days from reunion.

A Boy Shanghaied

James Wright lived with his widowed mother, Mrs. A. Wright, at 759 Harrison Street in Seattle. Until early 1905 he was an ordinary schoolboy, attending Mercer School. Sometime that winter, lured perhaps by tales of the sea or simply by the promise of a few dollars, the fifteen-year-old traveled up to Port Townsend. There, in the rough waterfront boarding houses and crimping dens that still flourished despite growing outrage, he was forced or coerced aboard a British sailing ship bound for Australia. The practice known as “shanghaiing” was illegal but common; boys and men were routinely kidnapped and forced to work as sailors for months or years at sea.

For the next year James sailed “before the mast” on windjammers, enduring the dangers and brutal discipline of deep-water sailing. From Australia he signed on another vessel to Callao, Peru. Stranded and penniless in South America, he appealed through American consular officials for help. The State Department eventually intervened, advancing small sums that allowed him to work his passage northward, first to Panama and then to San Francisco.

“This is my last trip on water”

He arrived in San Francisco about three weeks before Christmas 1905, exhausted, broke, and thoroughly cured of any romance the sea might once have held. He immediately wrote to his mother. Mrs. Wright wired money at once, enough for a second-class ticket home on the coastal steamer Valencia, scheduled to sail north on 20 January 1906.

A boyhood friend accompanied James to the dock. As they said goodbye, James told him, “This is my last trip on water. I’m sick of the sea and am going back home to make mother happy.”

The Final Voyage

The Valencia left San Francisco on schedule, but thick fog, bad weather and a fatal navigational misjudgement by the Captain resulted in the disaster. Just before midnight on 22 January she smashed onto the rocks near Pachena Point, Vancouver Island. Over the next thirty-six hours passengers and crew endured a nightmare of broken lifeboats, drowning in the surf and failed rescue attempts. Mostly women and children were put into the first boats; almost all were horrifically killed when the boats smashed against the Valencia or overturned in the crashing seas. James Wright, traveling second class and only sixteen, would have had little chance in the panic and almost none once the ship began to break up. No survivor ever reported seeing him after the wreck. His name appeared on every subsequent list of the lost.

A Sister’s Gesture, a Government’s Shame

In March 1906, James’s older sister, Miss Ella Wright, discovered that the State Department had spent $43.34 helping her brother escape South America the previous year. Wanting no debt to hang over the family, she mailed a check in reimbursement. C. H. Humphrey, a Washington state official who had taken up the Wrights’ cause, returned the money with a stinging letter to the Assistant Secretary of State:

“The government’s neglect in not protecting Pacific coast shipping is responsible for the grief of young Wright’s widowed mother and sister.”

Humphrey refused to allow the family to repay even the small sum spent to save James from Peru, declaring that if the department insisted, he would cover it himself rather than burden “the family of the victim of the Valencia disaster.”

The letter was widely reprinted. Coming so soon after the Valencia horror—one of the worst maritime disasters in Pacific Northwest history—it added one more voice to the public outcry that finally forced the creation of more lighthouses, life-saving stations and a rescue trail along the coast of Vancouver Island known today as the West Coast Trail. The West Coast Trail hugs the magnificently wild and most deadly section of coast in the treacherous “Graveyard of the Pacific”.

James Floyd Wright was sixteen years old. He had sailed halfway around the world against his will, survived storms, cruelty, and poverty, and was only days from home when the sea claimed him after all.

His mother kept vigil for months, hoping against hope that some miracle had carried him to shore unidentified. No such miracle came. Like scores of his fellow passengers, James simply vanished into the cold waters off Vancouver Island.

He remains there still—one of the Valencia’s nameless ghosts, a boy who had seen too much of the ocean and only wanted to come home to his mother.