![]() When shipping in and out of Juan de Fuca Strait rapidly increased in the mid 1800's and an alarming and costly number of ships were lost, the need for a inland trail was realized. It would take decades, and many more brutal and costly shipwrecks in the waters leading to Juan de Fuca Strait, to finally construct a life saving trail. The West Coast Trail has a wonderfully, horrifically, brutally, and certainly lengthy history.

When shipping in and out of Juan de Fuca Strait rapidly increased in the mid 1800's and an alarming and costly number of ships were lost, the need for a inland trail was realized. It would take decades, and many more brutal and costly shipwrecks in the waters leading to Juan de Fuca Strait, to finally construct a life saving trail. The West Coast Trail has a wonderfully, horrifically, brutally, and certainly lengthy history.

Prologue

Prologue Chapter 1: The West Coast Trail

Chapter 1: The West Coast Trail Chapter 2: When to Hike & Fees

Chapter 2: When to Hike & Fees Chapter 3: Trailheads

Chapter 3: Trailheads Chapter 4: Getting There

Chapter 4: Getting There Chapter 5: Considerations

Chapter 5: Considerations Chapter 6: Campsites

Chapter 6: Campsites Chapter 7: Shipwrecks

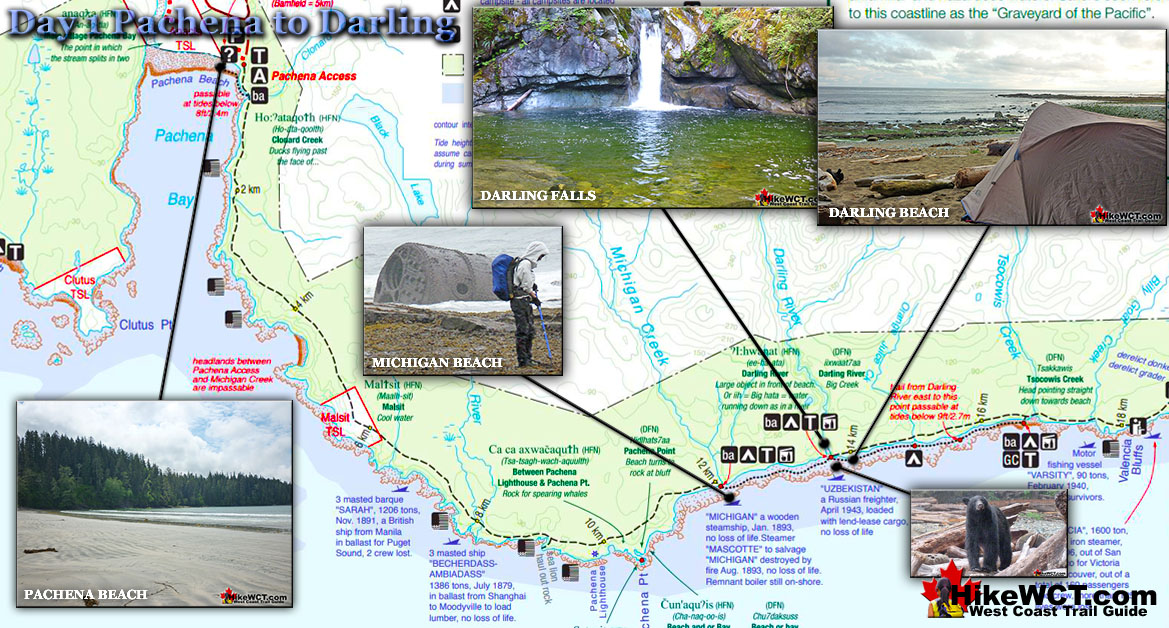

Chapter 7: Shipwrecks Chapter 8: Routes

Chapter 8: Routes Chapter 9: Sights & Highlights

Chapter 9: Sights & Highlights

The stretch of the Pacific from Vancouver Island to Oregon earned the name Graveyard Of The Pacific because of the shockingly frequent shipwrecks. To get that name. To earn such a horribly poignant name, a stretch of ocean had to have claimed a lot of ships in a small amount of time.

It did. And the reason it did is because of a unique set of circumstances. In short, if you were to design a part of the world to devour ships. To pull them into an inescapable death. Well, you'd do well to design it very much like Juan de Fuca Strait.

Step 1: have a major port of trade centre itself in a place like Vancouver. Or better yet, create two cities, one like Vancouver, and another like Victoria.

Step 2: have them located at the edge of a relatively unknown continent in the biggest ocean in the world.

Step 3: have these major cities accessed by entering a strait with a fast moving current and brutal weather half of the year.

Step 4: and this is the master stroke. Have the entrance to the straight be a lee shore with a brutally hostile, rocky shoreline, and as one last brutal stroke of evil. Make the current in the strait move northward toward the destructive coast. And make the current move faster as the weather gets worse, which it is a lot.

The Brutal History of Juan de Fuca Strait

Juan de Fuca Strait is all of these. It is a testament to how wonderful the cities of Vancouver and Victoria are. Not only did they rise out of such a brutal history of shipwreck disaster. But more importantly. More amazingly. They led to the creation of the West Coast Trail. This fact may not sink in with suitable gravity with the average person. But walk the West Coast Trail and it will resonate. The purpose of the trail sticks in the back of your mind as you hike it. It has to. There are shipwrecks at every beach. This is surely impossible, an exaggeration. But it's not.

As you walk you are constantly reminded that it's a life saving trail. But it's too hard. Even with the deluxe, IKEA looking ladders and bridges it's hard. How could survivors crawl off the beach and walk this trail. The sobering answer is simple. They did. They had to. They survived. They crashed onto Vancouver Island. These shores. As their ship was bashed into the rocks, the made their way to the shore. Some died, some lived. We have an unbelievably detailed history of who did and didn't. Then they set off on the Dominion Life Saving Trail.

I notice a jagged piece of rusted metal, out of place on the cleanly rounded rocks. I pick it up as I would a McDonald's bag. It looked like a piece of trash a bit out of place. I would read later that this beach is strewn with the wreckage of the Uzbekistan. In April 1943 it was on it's way to Russia. Everyone survived that wreck. I look up, still holding the jagged piece of ship. What a shitty beach. Rocky, littered with logs. The Uzbekistan. Holding a piece of history. And just laying on the beach. Is it really part of a shipwreck? It seems so ordinary. A rusted triangle of metal, no longer than my arm. But it's here. In the middle of nowhere. Not really though. Far from anything, but the map says that this is where the Uzbekistan, a WWII cargo ship on its way to Russia met its end. Disintegrated on this shore in 1943. The rusted piece of metal seems so much like garbage. It has no defining look. It doesn't feel like anything special. Like a piece of history, like a shipwreck should. I drop the piece of shipwreck and at the same instant hear it.

The waves crash loud. I hadn't noticed as I considered the piece of wreckage, but the waves are loud. Loud and relentless. Looking up, my back at the distant crashing of a waterfall. I see the open ocean. The deep, ominously pounding waves. I look at the piece of rusted metal more closely. Turning in to see it in different angles. It feels more real now. As if I could find my way into how this piece of rusted metal came to be here. Sixty years later, rusting on my day one of the West Coast Trail.

The Uzbekistan Shipwreck

![]() The first indication of the horror to come that they had on the Uzbekistan that night was the penetrating horror of mangling metal on the brutal rocky coast that I saw before me now. Not so long ago, I tried to imagine, a massive WWII era ship, in total darkness, lumbering into these rocks. The crushing sound of mangling metal. The panic. As dawn broke the 50 on board made their way ashore with the help of the low tide. Rescue came for all 50 of the Uzbekistan. But the ship itself was crushed repeatedly until it disintegrated into the rocks forever. Not really forever though. As I looked at the rusted piece of metal with the crushing waves beyond. It came to me in a flash. The importance of this thing in my hand. Like some ultra real museum, the West Coast Trail is a jaw dropping journey through history.

The first indication of the horror to come that they had on the Uzbekistan that night was the penetrating horror of mangling metal on the brutal rocky coast that I saw before me now. Not so long ago, I tried to imagine, a massive WWII era ship, in total darkness, lumbering into these rocks. The crushing sound of mangling metal. The panic. As dawn broke the 50 on board made their way ashore with the help of the low tide. Rescue came for all 50 of the Uzbekistan. But the ship itself was crushed repeatedly until it disintegrated into the rocks forever. Not really forever though. As I looked at the rusted piece of metal with the crushing waves beyond. It came to me in a flash. The importance of this thing in my hand. Like some ultra real museum, the West Coast Trail is a jaw dropping journey through history.

To pick up a piece of the Uzbekistan, look out on the ocean where 50 people clamored for the shore. This place is amazing. The warmth of excitement came over me. Of knowing that you are in the midst of something real. And as if day one of the West Coast Trail couldn't get any better, it did.

Amazing and Hidden Darling Falls

It's a sound I would come to hear a lot on the West Coast Trail. But this was the first time I'd heard it. Loud, rushing water. I felt tired. I'd hiked a long way. I felt like I was grubby. I had started the trail lots of energy and excitement, but so far the West Coast Trail was a bit tame. I followed the sound of water. It was loud. I could see it came from where a river came out of trees. A massive, slow moving river, clear, wide, and slow moving, snaked out of the forest. I followed it into the trees. The river bed was full of rainforest wreckage. Massive trees strewn all around as the clear, beautiful emerald water flowed around. The loud, water crashing sound became louder. It must be a waterfall, but I couldn't see it. Then suddenly it came into view. Like a scene out of a movie. A perfect waterfall. A perfect pool.

Perfectly Wild Darling River

Darling River in this instant became the standard in which I would judge the West Coast Trail forever. So wild. So unexpected. So exciting. As I carefully made my way as close to the waterfall as I could, I couldn't believe how clear the water was. So impossibly green the rocks at the bottom were. So clear the water was. In seconds I dove in. It was amazing. The perfect waterfall. As the wash of the falls pushed me away I fought the current of Darling River as it flowed out of this amazing green pool toward the ocean. I let the water carry me even as I swam with the river current toward the ocean.

The sun broke through the clouds in one of those bizarre moments of rain and sunshine. I swam with the current as it snaked through a wasteland of enormous logs. Ducking under a massive tree, rolling onto my back, staring up to the sun surrounded by a small patch of blue sky in an otherwise cloudy sky. Pushed with the current I watched the trees above move slowly. Incredibly, the perfect day. How exciting. So far the West Coast Trail couldn't be better. But it seems everything can get better. Or at least more bizarre, and this moment did.

The trees above widened and I realized I was passing through the beach and into the ocean. I twisted against the current as Darling River opened up into the ocean. Moving faster I thought in an instant that I'd be pushed into the ocean, then it hit me. A huge wave crashed against me. In an instant I wasn't moving either way. I'd hit the point where Darling River met the ocean waves. Bashing currents and waves made me stumble, feet sinking into the sand and gravel quicksand. I fell forward against the current and with waves crashing over my back and suddenly saw it. The piece of metal. The piece of Uzbekistan that I held a few minutes ago moving amongst the rocks and waves. I suddenly felt cold. The water was freezing despite the warmth of June. I stumbled toward the piece of wreckage pulling it from the waves. Holding it I suddenly felt some sort of connection. Crawling out of the ocean, looking on the same shore and trees they looked at all those years ago. I felt connected to them. Like the 50 survivors of the Uzbekistan I was crawling out of the ocean. In a surreal moment I picked up the piece of Uzbekistan and held it up to the shoreline. What a place this is. My first day on the trail and I've found a piece of shipwreck and a waterfall.

I stumbled forward, knee deep in the perfectly clear Darling River. I jumped in a few minutes ago next to the waterfall surrounded by trees and cliffs. Now I was out on the open beach. Looking left and right I could see for a couple kilometres in both directions. There was no one in sight, just as it would have looked for the survivors of the Uzbekistan. Looking now, I couldn't believe how far I'd moved in the river. There was a ways to go to get to my pack I left where I would spend my first night, at least a five minute walk. Tired and cold now I walked faster. What a crazy place this is, Darling River. How had I not read about Darling Falls before? No West Coast Trail books even mention it and only recently have websites mentioned it, but only barely.

Hidden Shipwrecks Along the West Coast Trail

The shipwrecks I had passed already since the trailhead have very interesting histories. At about 4km into the West Coast Trail from the Pachena trailhead look out to the ocean and you will spot the aptly named Seabird Rocks. This almost island marks the final resting place of two West Coast Trail shipwrecks. The Alaskan shipwreck lays at the bottom of the ocean about 300 metres to the right of the rocks and the Soquel shipwreck lies under the water just past the rocks.

The Alaskan Shipwreck

![]() The Alaskan was a small, wooden hulled steamship of 150 tons built in Oregon in 1886. She was owned by a Vancouver freight company and was enroute to Barkley Sound with 100 tons of box shooks(metal fittings to construct wooden crates). The Alaskan was last seen from Pachena Point apparently unable to round Cape Beale due to high winds she had turned back. Though distress flares were seen, no one witnessed its destruction and she evidently sunk killing the entire crew of 11. Three bodies washed ashore with considerable debris on the beaches west of Pachena Point.

The Alaskan was a small, wooden hulled steamship of 150 tons built in Oregon in 1886. She was owned by a Vancouver freight company and was enroute to Barkley Sound with 100 tons of box shooks(metal fittings to construct wooden crates). The Alaskan was last seen from Pachena Point apparently unable to round Cape Beale due to high winds she had turned back. Though distress flares were seen, no one witnessed its destruction and she evidently sunk killing the entire crew of 11. Three bodies washed ashore with considerable debris on the beaches west of Pachena Point.

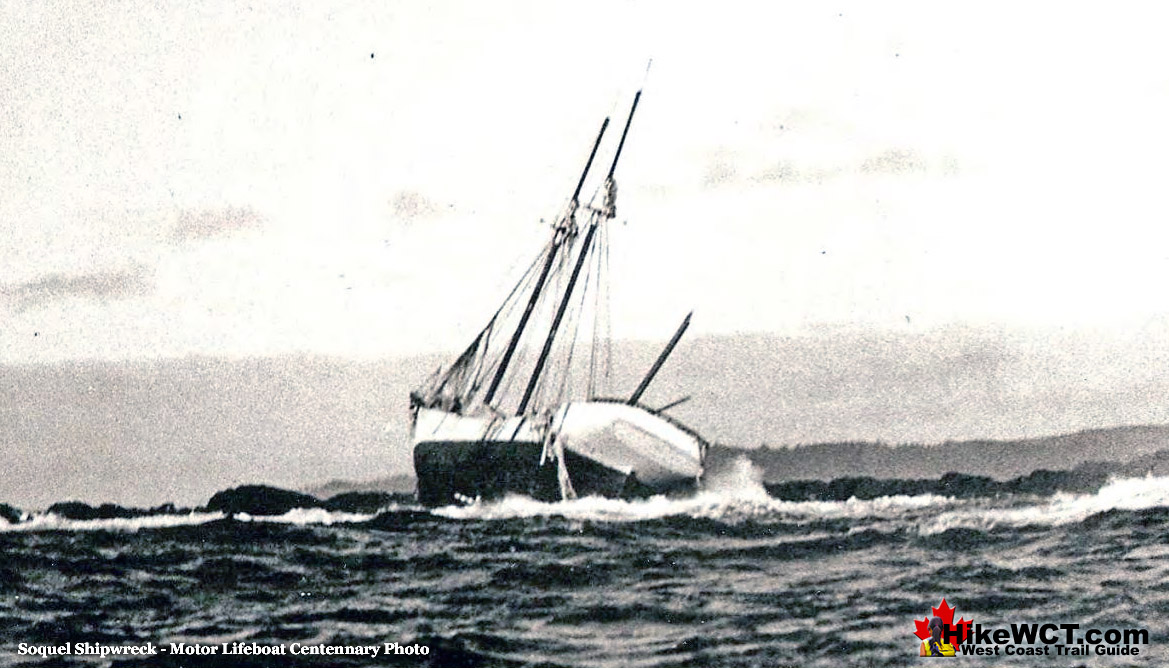

The Soquel Shipwreck

![]() The Soquel shipwreck which lies just past the Seabird Rocks was a much larger ship then the Alaskan at 698 tons. She was a four masted schooner built in San Francisco, California in 1902. She was sailing with ballast from Callao, Peru, heading for Port Townsend (near Seattle), when bad weather and high seas carried her far off course. The captains wife and daughter were killed by falling spars as two of the ships masts came crashing down. The next morning daylight revealed the Soquel on Seabird Rocks and a steam ship with a lifesaving crew from Bamfield was sent to rescue survivors. The single ship was unable to help anyone until another steamer arrived and both ships working together managed to pull 5 people off the reefs before the daylight faded. The next morning calmer seas enable the rescue the remaining survivors as well as the two dead bodies.

The Soquel shipwreck which lies just past the Seabird Rocks was a much larger ship then the Alaskan at 698 tons. She was a four masted schooner built in San Francisco, California in 1902. She was sailing with ballast from Callao, Peru, heading for Port Townsend (near Seattle), when bad weather and high seas carried her far off course. The captains wife and daughter were killed by falling spars as two of the ships masts came crashing down. The next morning daylight revealed the Soquel on Seabird Rocks and a steam ship with a lifesaving crew from Bamfield was sent to rescue survivors. The single ship was unable to help anyone until another steamer arrived and both ships working together managed to pull 5 people off the reefs before the daylight faded. The next morning calmer seas enable the rescue the remaining survivors as well as the two dead bodies.

The Sarah Shipwreck

![]() At about 7km into the West Coast Trail you will come to the shipwreck of the Sarah hidden under the waves near the shoreline. This three masted barque of 1206 tons, built in Nova Scotia in 1874. This British ship was sailing from the Philippines, heading for the Puget Sound. The captain sighted the recently built Carmanah Point Lighthouse and mistook it for the Cape Flattery Lighthouse. The ocean current had moved the ship considerably far north and when unexpected breakers were heard, the ships anchors were dropped. But it was too late, the Sarah ran aground on the shore of what is now the West Coast Trail. Over the next two days the crew of 18 and the captain's wife and baby managed to get ashore safely with the exception of two crew drowning.

At about 7km into the West Coast Trail you will come to the shipwreck of the Sarah hidden under the waves near the shoreline. This three masted barque of 1206 tons, built in Nova Scotia in 1874. This British ship was sailing from the Philippines, heading for the Puget Sound. The captain sighted the recently built Carmanah Point Lighthouse and mistook it for the Cape Flattery Lighthouse. The ocean current had moved the ship considerably far north and when unexpected breakers were heard, the ships anchors were dropped. But it was too late, the Sarah ran aground on the shore of what is now the West Coast Trail. Over the next two days the crew of 18 and the captain's wife and baby managed to get ashore safely with the exception of two crew drowning.

The Becherdass-Ambiadass Shipwreck

![]() Built in New Brunswick in 1864 the 1376 ton 3 masted ship the Becherdass-Ambiadass was wrecked on the rocky shore only a half mile from Pachena Point. This British ship was returning from Shanghai to Moodyville (now North Vancouver) when Cape Beale Lighthouse was sighted. As she neared Vancouver Island early morning fog blinded her and under full sail collided with the abruptly rocky shore near the 8km mark of the West Coast Trail. Amazingly no one was seriously hurt, but the ship was wrecked. The crew used the lifeboats to save themselves. The next day a local boat carried both the crew and their belongings to Victoria. In the following weeks the ship disintegrated on the rocks.

Built in New Brunswick in 1864 the 1376 ton 3 masted ship the Becherdass-Ambiadass was wrecked on the rocky shore only a half mile from Pachena Point. This British ship was returning from Shanghai to Moodyville (now North Vancouver) when Cape Beale Lighthouse was sighted. As she neared Vancouver Island early morning fog blinded her and under full sail collided with the abruptly rocky shore near the 8km mark of the West Coast Trail. Amazingly no one was seriously hurt, but the ship was wrecked. The crew used the lifeboats to save themselves. The next day a local boat carried both the crew and their belongings to Victoria. In the following weeks the ship disintegrated on the rocks.

The Michigan Shipwreck

![]() The Michigan shipwreck on the West Coast Trail is likely the first one you will see and actually touch, which is incredible since it is well over a century old. On January 21st, 1893 this 695 ton steam schooner was heading to Puget Sound from San Francisco. The strong northerly current that prevails in this part of the Pacific and would eventually cause dozens of shipwrecks, caused the Michigan to massively overrun her position. Instead of sailing into Juan de Fuca Strait, she collided with Vancouver Island in the middle of the night. The 25 people on board managed to get ashore after daylight. The seas calmed the crew was able to retrieve a boat from the wreck and was able to get to Neah Bay for assistance. A ship rescue was attempted, but was not successful. One death resulted from the attempt to hike over the old telegraph trail to Carmanah Point Lighthouse. A testament to how difficult it was then as compared to how relatively easy, the now relatively easy, West Coast Trail.

The Michigan shipwreck on the West Coast Trail is likely the first one you will see and actually touch, which is incredible since it is well over a century old. On January 21st, 1893 this 695 ton steam schooner was heading to Puget Sound from San Francisco. The strong northerly current that prevails in this part of the Pacific and would eventually cause dozens of shipwrecks, caused the Michigan to massively overrun her position. Instead of sailing into Juan de Fuca Strait, she collided with Vancouver Island in the middle of the night. The 25 people on board managed to get ashore after daylight. The seas calmed the crew was able to retrieve a boat from the wreck and was able to get to Neah Bay for assistance. A ship rescue was attempted, but was not successful. One death resulted from the attempt to hike over the old telegraph trail to Carmanah Point Lighthouse. A testament to how difficult it was then as compared to how relatively easy, the now relatively easy, West Coast Trail.

I woke at 8am to pouring rain. I knew it was coming. Here it was. Hard rain so characteristic of the West Coast Trail. I went back to sleep. It passed, but it took a few hours. At noon, with the tick, tick, tick of water hitting the tent, I emerged. I was still alive with the excitement of it all. With the rain fading, it was getting warmer. I made my way to the waterfall again and had another swim. Was this what everyday on the WCT was going to be like? I wanted to stay another night at this spectacular spot, but decided to push on. The next overnight stop was Tsusiat Falls. The amazing falls that are shown on half the photos of the WCT. I pushed on. Day one on the West Coast Trail was amazing. Next: The West Coast Trail

West Coast Trail Guide

Explore BC Hiking Destinations!

The West Coast Trail

Victoria Hiking Trails

Clayoquot Hiking Trails

Whistler Hiking Trails

Squamish Hiking Trails

Vancouver Hiking Trails