![]() All six boats launched in the first frantic 30 minutes after the Valencia wrecked were smashed against the ship or flipped and smashed against the base of the solid rock cliffs along the shore. Lifeboats No.1, No.4 and the working boat No. 7 were haphazardly released or cut free causing them to fall by one end and tossing the passengers into the water drowning all but one. Passengers watched in horror as dozens of people, many of them woman and children disappeared into the swirling ocean next to the ship.

All six boats launched in the first frantic 30 minutes after the Valencia wrecked were smashed against the ship or flipped and smashed against the base of the solid rock cliffs along the shore. Lifeboats No.1, No.4 and the working boat No. 7 were haphazardly released or cut free causing them to fall by one end and tossing the passengers into the water drowning all but one. Passengers watched in horror as dozens of people, many of them woman and children disappeared into the swirling ocean next to the ship.

The Valencia Disaster

![]() 1. The Valencia

1. The Valencia ![]() 2. The Voyage

2. The Voyage ![]() 3. The Boats

3. The Boats ![]() 4. The McCarthy Boat

4. The McCarthy Boat ![]() 5. The Bunker Party

5. The Bunker Party ![]() 6. On the Valencia

6. On the Valencia ![]() 7. The Rafts

7. The Rafts ![]() 8. The Turret Raft

8. The Turret Raft ![]() 9. The Rescue Ships

9. The Rescue Ships ![]() 10. The Aftermath

10. The Aftermath ![]() 11. The Survivors

11. The Survivors ![]() 12. The Lost

12. The Lost

The West Coast Trail

![]() Prologue

Prologue ![]() 1: The West Coast Trail

1: The West Coast Trail ![]() 2: When to Hike & Fees

2: When to Hike & Fees ![]() 3: Trailheads

3: Trailheads ![]() 4: Getting There

4: Getting There ![]() 5: Considerations

5: Considerations ![]() 6: Campsites

6: Campsites ![]() 7: Shipwrecks

7: Shipwrecks ![]() 8: Routes

8: Routes ![]() 9: Sights & Highlights

9: Sights & Highlights

Three boats were successfully launched during this time with an estimated 50 people on board. These were boats No.2, No.3 and No.6. All three managed to pull away from the ship for some distance until boats 3 and 6 were flipped over by waves. Boat No.2 is thought to have been flipped as well, however the Valencia’s power went out causing the spotlight on the boat to go dark and it vanished into the night. Though the frantic people still on board the Valencia did not know it, eleven people survived from the boats. One man made it to the rocky shore near the Valencia at the base of a tall cliff. Ten others were thrown onto the shore about 250 metres northwest of the Valencia out of sight due to a small point of land separating them. Remaining on board were an estimated 90 to 110 people. They had just witnessed 60 to 80 people drown or disappear into the night and six of their seven lifeboats destroyed or lost. Survivors later testified that this all occurred within 30 minutes of backing onto the reef. With the time just a few minutes after midnight and the ship’s power gone, they had only two small hand lamps to wait out the night. The survivors were mostly located in the dining saloon and what food that could be salvaged was shared around. Most of the food and supplies on the Valencia were already under water or inaccessible. Throughout the night the ship was hammered by the ocean and quickly breaking apart, settling lower. By Tuesday morning water was rising into the saloon and passengers had to move higher and higher on the ship. People packed into the small staterooms on the saloon deck and most were forced onto the hurricane deck.

During the night rockets and flares were set off in an attempt to attract help from the sea or shore. The captain and crew also hoped to get a glimpse of the coastline in the hopes of getting a clue of their location and a look at the nearby shore. As morning approached the Valencia began breaking apart. The bridge, pilot house, chart house and forward house were being torn from the hull. Huge swells were crashing over the bow and relentlessly smashing apart the upper parts of the ship. The situation on the ship was getting more and more desperate. Throughout the night the mood was quiet and calm, however the mood was changing as the ship crumbled away under them.

As light appeared in the morning one man was sighted on the reef at the base of the cliff across from the ship. The 29 January Victoria Daily Times reported on what Frank Connors remembered, “A member of the crew called Lewis, who Mr. Connors thinks was Lewis Oleson getting into a place of safety on the face of the rock, tried to drag this line in, but his efforts were useless. This line also parted. It has always been a mystery how Lewis reached this place of safety. Connors says he saw him attempt to cross a narrow strip of water which from the ship looked to be only about five feet wide. It looked as though he could jump across and from the other side could reach the top of the bluff. He was advised to do this, but apparently the distance was greater than it appeared from the ship. Lewis stripped off his gum boots and some other clothing and attempted to swim the gulf. He was immediately dashed to death.”

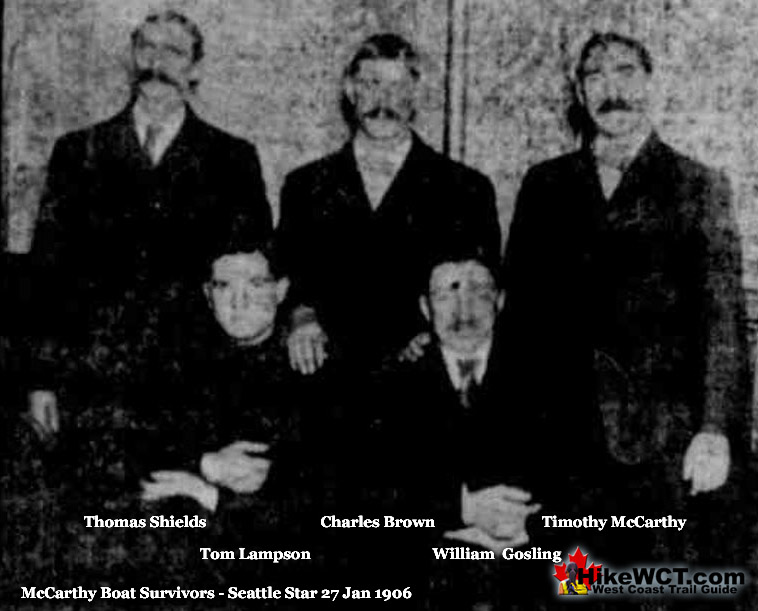

Sometime after 8am on Tuesday morning, January 23rd, the captain decided to launch the last lifeboat, the No.5 with a crew of men to find a way to land on shore and hike up to the cliffs opposite the ship. The Valencia was equipped with a Lyle gun which fired harpoons up to 1500 feet with a rope attached. If someone could receive the rope, they could pull it up and it would be connected to a heavy rope. This heavy rope could be tied to a tree and then the passengers could be winched up one at a time to the top of the cliff. When the captain first suggested this plan and asked for volunteers, no one came forward due to the six boats just hours ago meeting with disaster. Far from being cowardly, it must have been assumed that this boat would be smashed by breakers as the others had been and their occupants drowned. As boatswain Timothy McCarthy recalled how Captain Johnson pleaded for volunteers to take the last boat out to reach the shore to receive a line from the ship. Nobody volunteered. McCarthy testified later at the Valencia inquiry, “Meanwhile the seas were pounding on the ship and the captain came to me and said “I believe if you could get ashore some way you could help get a line attached.” Finally, he said: “Will you go in the boat?” I said “I’ll try.” "I asked two of the crew to come with me who at first declined. When Brown volunteered, they all offered to come with me in boat No.5. After making arrangements for using the Lyle gun the captain instructed me to prepare the boat.”

Lifeboat No.5 was prepared and to be manned by boatswain Timothy McCarthy and six brave crewmen, Thomas Shields, John Marks, William Gosling, Tom Lampson, Charles Brown and John Montgomery. All the men boarded the boat except John Montgomery, who was helping with the difficult launching off the starboard side of the ship. With the heaving ocean slamming into the Valencia with its stern lodged on the reef and the rest of the ship at a steep downward angle, mostly submerged, launching the boat was extremely difficult. Added to that you have the brutally cold weather and sleet falling. Montgomery was manning one of the falls, the rope and pulley system on either end of the lifeboat used to lower it into heaving seas below.

The trick was getting the boat to the water and quickly away from the ship before it can get smashed into it by a huge wave. Montgomery needed to slide down the falls in the few critical seconds between it hitting the water and releasing the ropes to get away from the ship. As soon as the boat hit the water, Montgomery quickly leaped over and began his short but terrifying descent. He was not fast enough, and that combined with frozen hands and wet ropes, he plunged into the sea and was swept to his death.

Lifeboat No.5, manned with six men now faced the formidable breakers. Rowing hard out to sea they managed to smash over the breakers and into the open ocean. With the fear of being flipped in the breakers behind them, they rowed west up the coast looking for a safe shore to land. Onlookers from the Valencia and the men on the lifeboat would later report that leaving the ship and rowing hard for about 100 yards to get past the breakers was challenging, but not overly difficult. Some water came over the sides, but not enough to require bailing and they never felt in serious danger while crossing the line of breakers. Despite this success, they evidently remained terrified of the breakers that they knew they had to cross as soon as possible to get to shore.

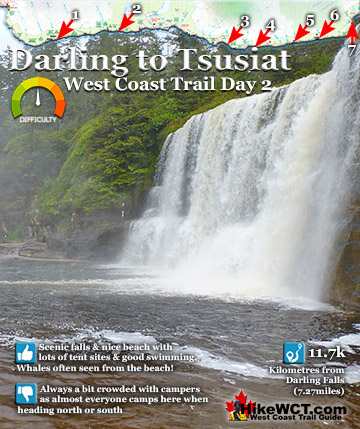

They kept well outside the breakers and rowed their way up the coast, not making any attempts at a landing. After rowing 7 miles along what they believed was the coast of Washington State, they reached a large bay which they would soon find out was Pachena Bay on Vancouver Island. There they spotted a short strip of beach and made a landing on the westward shore near the mouth of the bay somewhere between noon and 1pm. Looking for a trail to exit the beach they found a sign that read, “Three Miles to Cape Beale”. This was when they discovered their true location along the west coast of Vancouver Island. With just 3 miles to the Cape Beale Lighthouse, they chose to hike there to seek help instead of attempting to hike back to the Valencia. The route back to the Valencia was only indicated by a telegraph line draped between trees and disappearing into the forest. A forest that they later described as impenetrable, which it largely would have been in 1906. To reach the Valencia they would have had to claw their way through the forest for more than 18 kilometres. This route would have been unmarked, overgrown and lacking the elaborate network of ladders and bridges that we see today.

The choice to head to the lighthouse was the only realistic choice for them at that time. They did however, let down the survivors on the Valencia and fail to make a close landing and hike up to the cliffs to receive the line fired from the ship. Just a mile up the coast from the Valencia a beach extends from Tsocowis Creek to Michigan Creek for 5 kilometres. Had they attempted to reach shore along this section they would have had only 2 kilometres of difficult rainforest hiking to reach the cliffs above the Valencia. With the condition of the trail in 1906 and in the winter with several centimetres of snow on the ground, this may have been extremely difficult. The beach would have been obscured by the breakers and it seems likely that they didn’t want to risk losing the boat and landing at similar cliffs near the Valencia. They must have known that in their weakened condition and in bad weather they were not going to hike to the Valencia after rowing just a couple miles, let alone the 7 miles they went. Not attempting to land before 7 miles seems odd, considering that the stated purpose was specifically to make a nearby landing and hike to the cliffs to receive the line. It surely was a terrifying prospect to steer into the breakers and cast toward an unknown shore and a likely death. It must also be remembered that just hours ago they witnessed scores of people die in this way. They hiked the trail to the Cape Beale Lighthouse and arrived at about 3pm. They reported the wreck to the lighthouse keeper and the news was telegraphed to the nearby town Bamfield, who let them know that they had already received a report an hour earlier from a shore party that reached the lineman’s hut at Darling River. A party of nine men that survived from the boats the previous night had managed to follow the telegraph line to reach a lineman’s hut 5 kilometres up the coast at Darling River. They had reported the wreck at 2pm, Tuesday the 23rd, just an hour before the McCarthy party did.

The McCarthy Boat Survivors (John Marks not in photo)

Continued: 5. The Bunker Party

Best West Coast Trail Sights & Highlights

The Valencia Disaster

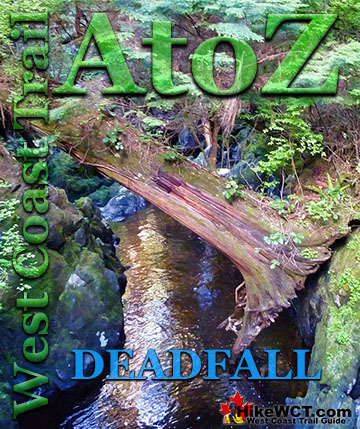

West Coast Trail A to Z

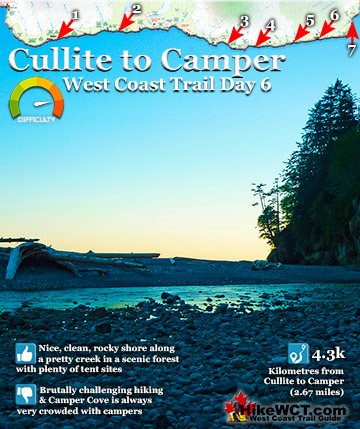

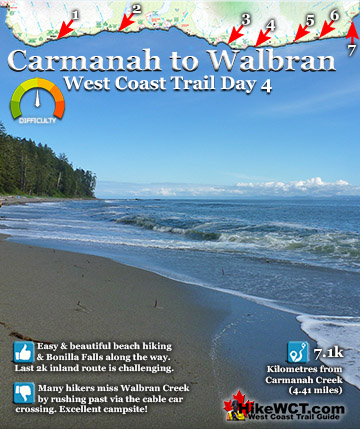

The West Coast Trail by Day

Explore BC Hiking Destinations!

The West Coast Trail

Victoria Hiking Trails

Clayoquot Hiking Trails

Whistler Hiking Trails

Squamish Hiking Trails

Vancouver Hiking Trails