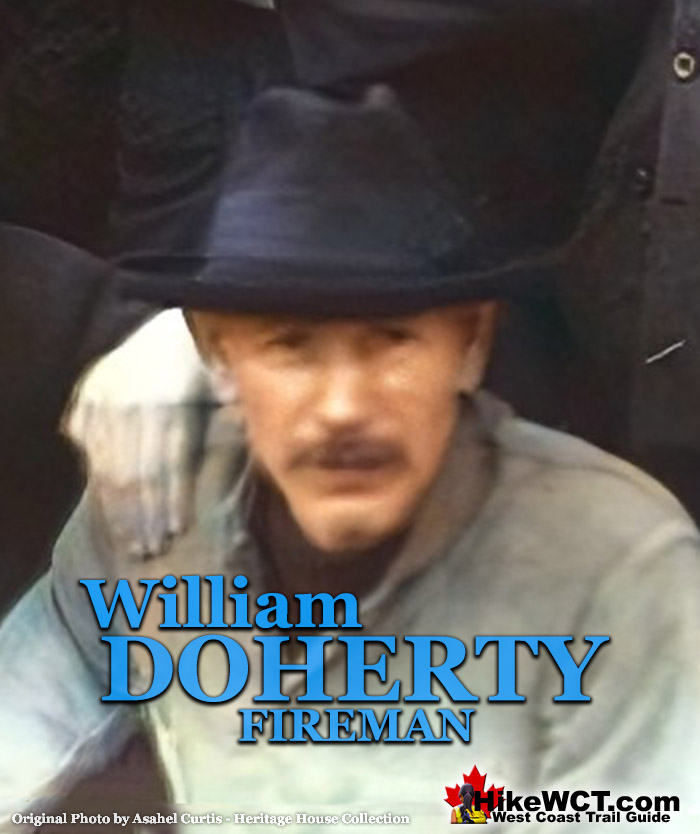

![]() William Doherty, a 40-year-old fireman with 22 years of experience on steamships, was one of the 19 survivors rescued by the steamship Topeka. His account sheds light on the chaos and survival efforts during the catastrophe. Doherty was in the engine room when the Valencia struck a reef, causing water to flood the fore part of the ship. He and his crewmates worked desperately to maintain steam pressure as the order came for “full speed astern,” prompting the ship to reverse rapidly.

William Doherty, a 40-year-old fireman with 22 years of experience on steamships, was one of the 19 survivors rescued by the steamship Topeka. His account sheds light on the chaos and survival efforts during the catastrophe. Doherty was in the engine room when the Valencia struck a reef, causing water to flood the fore part of the ship. He and his crewmates worked desperately to maintain steam pressure as the order came for “full speed astern,” prompting the ship to reverse rapidly.

The Valencia Disaster

![]() 1. The Valencia

1. The Valencia ![]() 2. The Voyage

2. The Voyage ![]() 3. The Boats

3. The Boats ![]() 4. The McCarthy Boat

4. The McCarthy Boat ![]() 5. The Bunker Party

5. The Bunker Party ![]() 6. On the Valencia

6. On the Valencia ![]() 7. The Rafts

7. The Rafts ![]() 8. The Turret Raft

8. The Turret Raft ![]() 9. The Rescue Ships

9. The Rescue Ships ![]() 10. The Aftermath

10. The Aftermath ![]() 11. The Survivors

11. The Survivors ![]() 12. The Lost

12. The Lost

The West Coast Trail

![]() Prologue

Prologue ![]() 1: The West Coast Trail

1: The West Coast Trail ![]() 2: When to Hike & Fees

2: When to Hike & Fees ![]() 3: Trailheads

3: Trailheads ![]() 4: Getting There

4: Getting There ![]() 5: Considerations

5: Considerations ![]() 6: Campsites

6: Campsites ![]() 7: Shipwrecks

7: Shipwrecks ![]() 8: Routes

8: Routes ![]() 9: Sights & Highlights

9: Sights & Highlights

Doherty survived by escaping on the second and final life raft launched from the Valencia. The Valencia’s life rafts were barely buoyant, sitting low in the water with submerged oars that were unusable. Survivors had to pull the oars from their locks and paddle clumsily. As the first raft departed, the captain fired the Lyle gun to signal the distant steamship Queen. Encouraged by the first raft’s success, six crewmen jumped onto the second raft to keep it clear of the ship. Despite pleas, no women boarded, with one woman, a friend of first assistant engineer Thomas Carrick, refusing hysterically after seeing the raft tossing in the violent waves.

The scene on the Valencia was chaotic. Carrick described the ship breaking apart, with only 15 feet of the hurricane deck left for 50–75 people. Second officer Peter Peterson barely made it onto the raft, weakened by hunger and exposure, while messman Walter Raymond nearly drowned but was hurled onto the raft by a wave. The raft, packed with 19 men, departed 20 minutes after the first.

Conditions on the overcrowded raft were brutal. Survivors stood waist-deep in freezing water, battered by breakers. The oars, lashed underwater, were cut loose and used by pairs of men braced by others. Carrick steered from the stern as they paddled toward the Queen, which disappeared, crushing morale. Passenger Cornelius Allison recalled the Queen steaming away without attempting rescue, despite being only three-quarters of a mile off.

After hours of exposure, some men showed signs of insanity, frothing at the mouth. Hope returned when the City of Topeka was sighted. Survivors paddled frantically, signaling with a shirt on a boat hook. The Topeka launched a boat, towing the raft to safety just as the men were succumbing to cold and exhaustion. Passenger Joseph McCaffrey described a delirious survivor singing as rescue neared, while others collapsed.

Topeka Lifeboat and Valencia's Second Raft January 24th 1906

Topeka Lifeboat and Valencia's Second Raft January 24th 1906

William Doherty was one of the 19 survivors rescued by the City of Topeka. The others were: passenger Cornelius Allison, first assistant engineer Thomas Carrick, second officer Peter Peterson, baker Charles Fluhme, passenger George Harraden, passenger A.H. Hawkins, waiter Charles Hoddinott, third cook John Johnson, coal passer W.D. Johnson, first assistant freight clerk Frank Lehn, passenger Joseph McCaffrey, waiter Patrick O'Brien, fireman Paul Primer, messman Walter Raymond, fireman John Segalos, fireman Max Stensler, quartermaster Martin Tarpey, waiter James Walsh and passenger Grant L. Willitts. The survivors were emaciated and tattered upon reaching Seattle. The Pacific Coast Company provided clothing, food, and lodging. Allison criticized the rescue ships, particularly the Queen and a nearby tug, for not approaching closer despite calm conditions. The Topeka Raft’s survival underscores the resilience of those who endured the disaster’s chaos and the sea’s unrelenting cruelty.

Some of Valencia's Crew on the Topeka