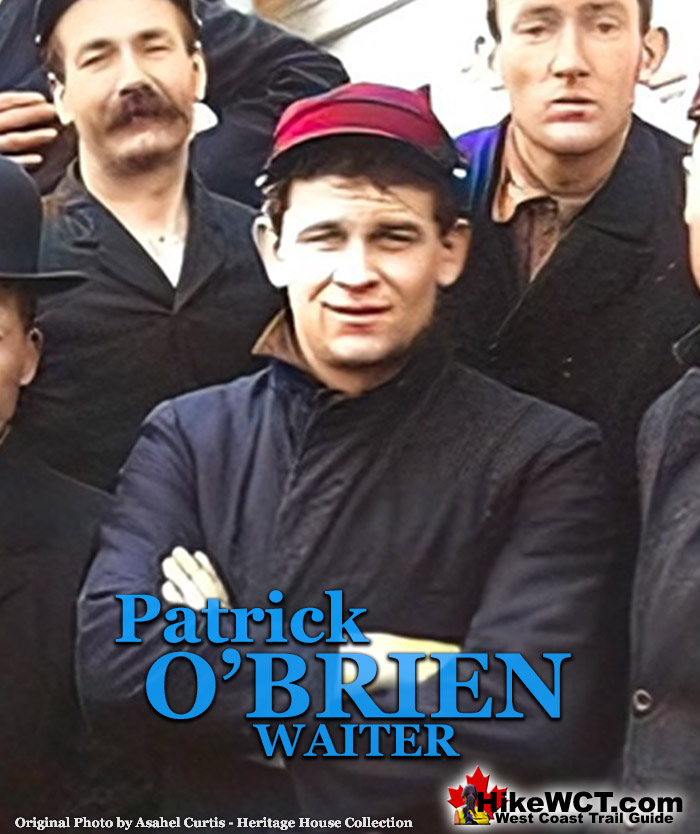

![]() Patrick O'Brien a waiter on the Valencia and one the life raft survivors picked up by the City of Topeka. Very little is known about him and he is rarely mentioned in newspapers and seems to have never been interviewed. His photo appears in a few newspapers, but nothing about him. We can only piece together his time on the Valencia from the experiences of other survivors.

Patrick O'Brien a waiter on the Valencia and one the life raft survivors picked up by the City of Topeka. Very little is known about him and he is rarely mentioned in newspapers and seems to have never been interviewed. His photo appears in a few newspapers, but nothing about him. We can only piece together his time on the Valencia from the experiences of other survivors.

The Valencia Disaster

![]() 1. The Valencia

1. The Valencia ![]() 2. The Voyage

2. The Voyage ![]() 3. The Boats

3. The Boats ![]() 4. The McCarthy Boat

4. The McCarthy Boat ![]() 5. The Bunker Party

5. The Bunker Party ![]() 6. On the Valencia

6. On the Valencia ![]() 7. The Rafts

7. The Rafts ![]() 8. The Turret Raft

8. The Turret Raft ![]() 9. The Rescue Ships

9. The Rescue Ships ![]() 10. The Aftermath

10. The Aftermath ![]() 11. The Survivors

11. The Survivors ![]() 12. The Lost

12. The Lost

The West Coast Trail

![]() Prologue

Prologue ![]() 1: The West Coast Trail

1: The West Coast Trail ![]() 2: When to Hike & Fees

2: When to Hike & Fees ![]() 3: Trailheads

3: Trailheads ![]() 4: Getting There

4: Getting There ![]() 5: Considerations

5: Considerations ![]() 6: Campsites

6: Campsites ![]() 7: Shipwrecks

7: Shipwrecks ![]() 8: Routes

8: Routes ![]() 9: Sights & Highlights

9: Sights & Highlights

By 9 a.m. on Wednesday, January 24, after nearly 34 hours of relentless pounding by the Pacific waves, the ship was disintegrating. O'brien and 80 survivors clung desperately to the few remaining sections of the upper deck still above water, battered by crashing waves that threatened to sweep them away at any moment. Rescue ships appeared on the horizon, raising hopes among the survivors. The Queen, a large steamer, was the first to arrive, followed by the tug Czar and the salvage vessel Salvor. However, no rescue attempts were made. Thomas Carrick, the Valencia’s first assistant engineer, later recalled, “The Queen stood off about a mile and a half. I saw two boats swinging from the davits, as if ready to be lowered, but nothing happened.” Sam Hancock, the ship’s chief cook, added, “The Queen came within a reasonable distance and stopped. A tug approached us briefly but turned away. No boats were lowered.” Passenger Joseph McCaffrey, testifying at the Valencia inquiry, expressed his initial optimism: “When the Queen, Salvor, and Czar came into view, I thought rescue was imminent. The Czar might have been as close as 200 yards.”

Despite the proximity of the rescue ships, the worsening weather—shifting winds, choppy seas, and encroaching fog—prevented action. The Queen, a 300-foot vessel with a deep draft, couldn’t navigate the uncharted, rocky waters closer to the wreck. The Czar attempted to approach but was forced to retreat after taking on water. By 10:15 a.m., as the Valencia’s situation grew dire, the Salvor and Czar departed for Bamfield Creek to organize a land-based rescue, while the Queen lingered briefly before steaming away, ordered back to Victoria by company officials.

The Desperate Launch of the Life Rafts

With the Valencia breaking apart and no rescue forthcoming, the crew made a harrowing decision to launch their last two life rafts, known later as the Turret Raft and the Topeka Raft. These rafts, designed to float but not to shield occupants from the elements, left survivors partially submerged and exposed to freezing waves. Already exhausted, cold, and dehydrated, many aboard the Valencia hesitated to leap into the churning ocean to board the rafts, hoping instead for rescue from the nearby ships.

The Turret Raft: A Fragile Escape

The first raft, the Turret Raft, carried only 10 men—far below its estimated capacity of 18—due to the perilous boarding process. Survivors had to jump from the ship’s deck into the icy water, swim to the raft, and climb aboard while avoiding being crushed against the Valencia’s hull. The raft’s low buoyancy and unwieldy oars, rendered useless by submersion, made navigation treacherous. Despite these challenges, the Turret Raft miraculously cleared the breakers and drifted toward the open sea, its fate unknown to those left behind.

The Topeka Raft: A Crowded Struggle

Encouraged by the first raft’s departure, the crew prepared the second raft, the Topeka Raft, with renewed urgency. Six crewmen leapt into the water to stabilize the raft, but convincing others to follow proved difficult. Carrick recounted pleading with a young woman to board, only for her to flee in terror at the sight of the raft tossing violently below. Eventually, 19 men crowded onto the raft, which was designed for approximately 12. Conditions on the Topeka Raft were nightmarish. Carrick described the survivors standing waist-deep in freezing water, battered by waves, and unable to use the oars effectively. The men improvised, using oars as paddles while forming human “row-locks” to brace each other. Passenger Cornelius Allison recalled, “The water was so cold our limbs became numb. Huge seas buried us, and we choked on saltwater while trying to breathe.” After two agonizing hours, a shout from a passenger alerted the raft to the City of Topeka, a steamer searching the coast. The men rowed with desperate strength, waving a shirt tied to a boat hook to signal the ship. Initially, the Topeka seemed to turn away, plunging the survivors into despair. But then it approached, and a rescue boat was launched. Carrick recalled, “Some men were too weak to grasp the lines cast from the Topeka. If she hadn’t arrived when she did, we would all have succumbed to the cold.”

Nineteen Valencia Survivors Rescued by the Topeka

The nineteen men picked up by the second raft, which became known as the Topeka Raft were: waiter Patrick O’Brien, third cook John Johnson, passenger Cornelius Allison, first assistant engineer Tom Carrick, fireman William Doherty, baker Charles Fluhme, passenger George Harraden, passenger A.H. Hawkins, waiter Charles Hoddinott, coal passer W.D. Johnson, first assistant freight clerk Frank Lehn, passenger Joseph McCaffrey, , second officer Peter Peterson, fireman Paul Primer, messman Walter Raymond, quartermaster Martin Tarpey, waiter John Walsh, passenger Grant Willits and fireman John Segalos.

Twelve of the Topeka Raft Survivors